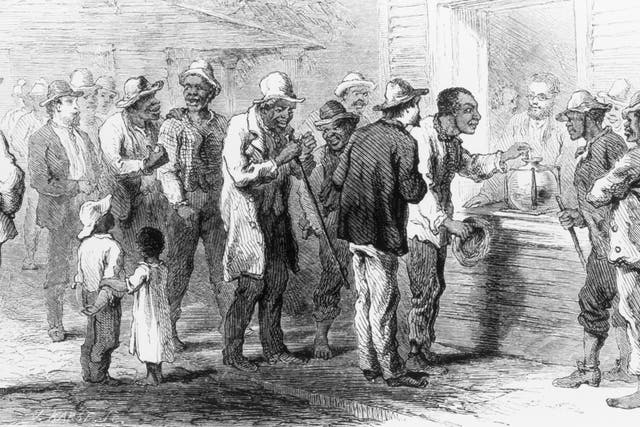

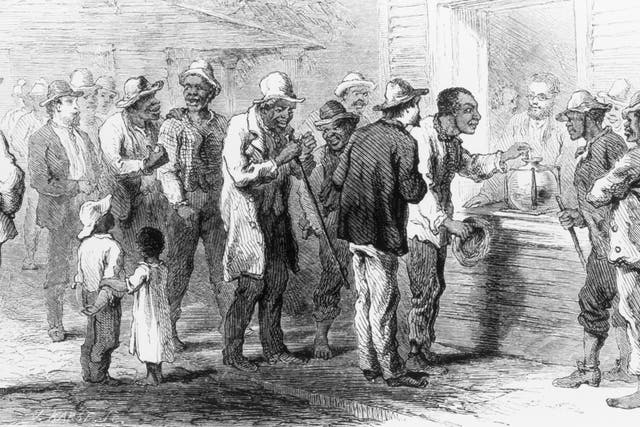

In the wake of the passage of the 15th Amendment and Reconstruction, several southern states enacted laws that restricted Black Americans' access to voting.

Updated: August 8, 2023 | Original: May 13, 2021

Following the ratification in 1870 of the 15 th Amendment, which barred states from depriving citizens the right to vote based on race, southern states began enacting measures such as poll taxes, literacy tests, all-white primaries, felony disenfranchisement laws, grandfather clauses, fraud and intimidation to keep African Americans from the polls.

Focused on retaining white supremacy in the electoral process, legislators used loopholes in the 15 th Amendment to implement a range of measures to disenfranchise Black voters without explicitly characterizing them on the basis of race.

Black CodesAfter more than a half million Black men joined the voting rolls during Reconstruction in the 1870s, helping to elect nearly 2,000 Black men to public office, Mississippi led the way in using measures to circumvent the 15 th Amendment. Mississippi's Jim Crow-era laws then set a precedent for other southern states to use the same tactics to assault Black enfranchisement for nearly a century until the passage of the Voting Rights of 1965.

At the 1890 Mississippi State Convention a new constitution was adopted that included a literacy test and poll tax for eligible voters. Under the new literacy requirement, a potential voter had to be able to read any section of the Mississippi Constitution or understand any section when read to him, or give a reasonable interpretation of any section.

“There is no use to equivocate or lie about the matter,” said James Vardaman in 1890. Vardaman served in the Mississippi Legislature at the time of convention and later became governor of the state. “In Mississippi we have in our constitution legislated against the racial peculiarities of the Negro. . . . When that device fails, we will resort to something else.”

The impact of the legislation was swift. By 1910, registered voters among African Americans dropped to 15 percent in Virginia, and under 2 percent in both Alabama and Mississippi, according to historian, Donald G. Nieman, in his book Promises to Keep: African-Americans and The Constitutional Order, 1776 to the Present.

In the 1898 Williams V. Mississippi ruling, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the state’s poll tax, disenfranchisement clauses, grandfather clause and literacy tests on the basis that the new constitution didn’t “discriminate between the races and it has been shown that their actual administration wasn’t evil: only that evil was possible under them.” The Williams ruling eased the implementation of voter-suppression statutes in many other southern states, including Louisiana, South Carolina, North Carolina, Alabama, Virginia and Georgia.

John B. Knox, an Alabama delegate to that state’s 1901 convention, revealed the mindset of white legislatures when he stated that, “The convention’s goal is to establish white supremacy in the State, within the limits imposed by the Federal Constitution.”

While many of the voting suppression measures could also impact poor white people, they disproportionately impacted African Americans.

Anti-literacy laws in many southern states made it illegal to teach enslaved people to read. In 1880, according to the U.S. Bureau of Census, 76 percent of southern African Americans were illiterate, a rate of 55 percent points greater than that for southern white people. In 1900, 50 percent of voting-age Black men could not read, compared to 12 percent of voting-aged white men. These disparities made literacy tests one of the most effective tools at suppressing the African American vote. The voting clerks, who were always white, could also pass or fail a person at their discretion based on race.

Illiterate white people were often excluded from these literacy tests through the use of grandfather clauses, which tied their voting rights to their grandfathers' before the Civil War. Former slaves, who had no voting rights until the 15 th Amendment, could obviously not benefit from this provision. The grandfather clause also applied to poll taxes, which were another measure created by white-dominated southern legislatures to suppress the Black vote.

While southern legislatures claimed that poll taxes for voting were designed to raise state revenue, to many white political leaders, the main purpose was to suppress the African American vote. “This newspaper believes in white supremacy,” said a Tuscaloosa (Alabama) News editorial in 1939, “and it believes that the poll tax is one of the essentials for the preservation of white supremacy.”

Eleven states in the South had laws that required citizens to pay a poll tax before they could vote. The taxes, which were $1 to $2 per year, disproportionately impacted Black registered voters. In Georgia, which implemented a cumulative poll tax in 1877 that required all citizens to pay back taxes before being permitted to vote, Black voter turnout went down 50 percent, according to Morgan Kousser in The Shaping of Southern Politics: Suffrage Restriction and the Establishment of the One-Party South, 1880-1910.

When literacy tests, poll taxes, grandfather clauses and the many other ways to circumvent the 15 th Amendment didn’t work to suppress Black voter turnout, white legislators in several southern states used all-white primaries to all but eliminate Black voters' presence in the electoral process.

In Texas, for example, the legislature gave the Democratic Party the authority to set its own rules. The party determined that it was for white voters only, excluding African Americans from its elections and effectively making local electoral politics dominated by one party that upheld Jim Crow laws.

After a white election official blocked a Black man, Lonnie E. Smith, the right to vote in the 1940 Texas Democratic primary, the NAACP's Thurgood Marshall and William H. Hastie challenged the case all the way to the Supreme Court. In 1944, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Smith V. Allwright that the Texas white primary system was unconstitutional.

“The right to vote in a primary for the nomination of candidates without discrimination by the State…is a right secured by the Constitution,” said the court in its 8-1 decision.

Signed into law 95 years after the 15 th Amendment was ratified into the Constitution, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 outlawed most discriminatory voting practices in southern states such as literacy tests, poll taxes, and grandfather clauses that had been designed by southern legislatures to suppress the African American vote.

Almost as swift as the resistance to Black voter participation had been nearly a century earlier, so had the response to this landmark legislation. Within a year, only four of the 13 southern states had fewer than 50 percent of African American registered voters.

In 2013, the U.S. Supreme Court walked back part of the Voting Rights Act when it ruled in a 5-4 vote that constraints placed on certain states and federal review of states’ voting procedures were outdated. In the wake of the Shelby County v. Holder decision, several states have enacted laws limiting voter access, including ID requirements, limits on early voting, mail-in voting and more.